Specimen Database

The Intermountain Herbarium began data basing its specimen information in 1990, using Alpha Database Software. We now use the SYMBIOTA database software via 4 portals:

- Vascular plants - intermountainbiota.org

- Fungi - mycoportal.org

- Lichens - lichenportal.org

- Bryophytes - bryophyteportal.org

As of November, 2018, we have 171,465 records in the database. This represents 60.9% of the specimens in the Herbarium. Of the databased records, 26% are of Utah specimens and 21% are of grasses. About 39% of the databased records are georeferenced (have latitude and longitude information), an essential for mapping distributions, and about 47% are imaged.

Our priority for entering specimens into the database are:

- specimens involved in a herbarium transaction (additions, annotations, loan preparation or return)

- Utah specimens

Our records are made available via the Global Biodiversity Information Facility and idigbio.

Holding Growth

Overall Growth

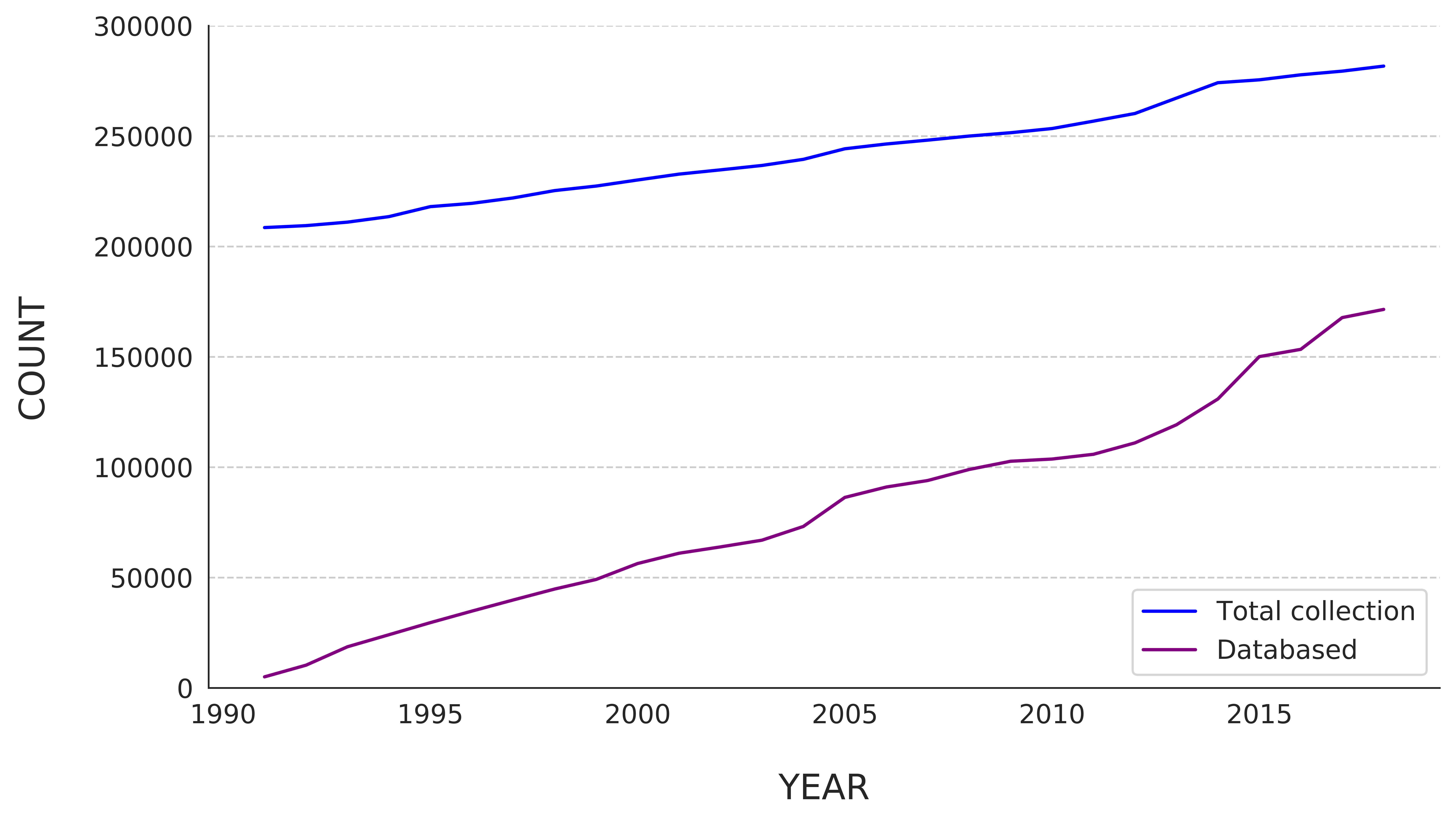

The approximately 280,000 specimens in the Intermountain Herbarium come primarily from western North America, but there are substantial holdings from other parts of the world. The average growth rate for the past five years has been slightly over 4,000 specimens per year (see graph below). 171,465 specimens are databased, 80,907 are imaged, and 67,860 are georeferenced.

Most specimens in the herbarium are of vascular plants, with approximately half coming from Utah and Nevada, the core states of the Intermountain Region.

Fungal Collection

The herbarium now has over 3,000 fungal specimens, nearly all of which have been databased. They come primarily from Dr. R. Fogel, an Emeritus Professor of the University of Michigan, and Michael Piep, the Assistant Curator, whose interests lie in the Macrofungi of Utah.

Lichen Collection

The lichen collection is small but growing slowly, consisting of slightly over 1,200 specimens, primarily from North America, with specimens from Wyoming, Arizona, and Utah comprising the greatest percentage. About half the specimens are duplicates of specimens collected by Nash.

Bryophyte Collection

The bryophyte collection is small, consisting of slightly over 2,200 specimens, occupying one cabinet. About half the specimens are duplicates of specimens collected by Flowers, author of Utah's Mosses and Hepaticae of Utah..

Types

Among its specimens, the herbarium has 81 holotypes and 1,176 isotypes. Most of the type specimens are vascular plants, but 17 of the holotypes and several of the isotypes are of fungi and lichens.

Holding Growth of Intermountain Herbarium 1991-2018

Fungi

The majority of fungal specimens in the Intermountain Herbarium are from the western United States - an estimated 74%. Utah specimens currently comprise over 50% of the specimens currently held.

The fungal collection has benefited by donation or transfer of a number of collections. These specimens have come from primarily four sources: transfer of most of the Univeristy plant and forest pathology teaching collection; a large gift of duplicates from the University of Michigan Herbarium and Dr. Robert Fogel; donation of the personal collection of Michael Piep; and collections from Don Johnston of the Mushroom Society of Utah.

The Intermountain Herbarium has been designated the official repository of voucher collections for both the Bridgerland Mushroom Society and the Utah Mushroom Society.

The collection comprises a large percentage of plant pathogens, reflecting the agricultural origins of Utah State University. These specimens come from five continents and 30 countries. A portion of the plant and forest pathology teaching collection has been transferred to the Herbarium and is currently being incorporated into the collection as time and resources permit. There are a large number of hypogeous collections reflecting the interest of Dr. Robert Fogel in these fascinating and ecologically important species.

Lichenized fungi and Myxomycetes comprise a very small portion of the holdings (less than 350 specimens). All of our myxomytes have been databased and we are currently working on the lichenized fungi as resources permit.

There is one cabinet of type specimens. We are currently reviewing the status of all specimens in the cabinets, removing those that are not truly types. For those that are types, we are noting which kind of type they are and placing a copy of the relevant publication in the reprint section of the Herbarium library. Once completed the listing will be available on the Web.

History

The Intermountain Herbarium was founded by Bassett Maguire in 1932. Taxonomy had been taught at the Utah Agricultural College before that time, using a collection of about 90 plants that had been provided by C.V. Piper, a botanist who developed the first floras for the Pacific Northwest and went on to work on the introduction and domestication of grasses for the USDA.

In 1932, Maguire persuaded the Utah Department of Agriculture and the Utah Agriculture Experiment Station stating that "Since the knowledge of the composition, and particularly the distribution, of our flora is inadequately known, and since such data are essential to proper administrative policies concerning state lands and to technical research which is fundamental to all agronomic activities, the immediate program of the herbarium shall consist of a preliminary plant survey of Utah".

When he filed the herbarium’s first annual report in June 1932, Maguire had assembled 10,432 specimens of which 5,682 had been mounted and filed prior to receiving official approval for the project. During the herbarium's first year as UAES Project 135, an additional 3,479 specimens were collected of which 2,147 had been mounted and incorporated into the collection. In 1943, Maguire went to the New York Botanical Garden to work on Utah plants. He eventually ended up staying there, becoming its director and developing a research program focused on Central andSouth America.

In 1948, Maguire was succeeded at the Intermountain Herbarium by one of his students, Arthur H. Holmgren, who remained in charge of the herbarium until his retirement in 1979. Holmgren carried on Maguire’s floristic emphasis, adding to the collection and preparing various publications on Utah’s plants.

In 1963, a staff position was add to the herbarium. This was first held by Bernice Anderson who worked with Holmgren on several popular publications on Utah’s plants. She was succeeded by Leila Shultz who conducted floristic research in the region and, after completing her doctorate, joined the College of Natural Resources as a research faculty member. The position is now held by Michael Piep.

Holmgren was initially succeeded by Barkworth but she was replaced by Richard J Shaw for a few years. During his tenure, Shaw completed work on his Vascular Plants of Northern Utah, a work that was used for almost 30 years in plant taxonomy classes at U.S.U. in addition to revising his checklists for Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. After Shaw’s retirement, Barkworth was reinstated as the Director of the Herbarium. Since her reappointment, one of her primary goals has been making the herbarium's resources and botanical knowledge more accessible. She is ably assisted in this respect by Michael Piep, the Assistant Curator since 2004, who draws on the knowledge and experience he gained as a botanical consultant, teacher, and mycologist in presenting talks and workshops as well as in identifying plants. Last year he added to these accomplishments by arranging a highly discounted price for some display cases – and then raising the money needed to purchase and refurbish them. With these cases, the herbarium will, we hope, succeed in attracting a more people to the fascinating world of plants and fungi.

The herbarium is particularly rich in grasses and literature about grasses. This started with Holmgren’s interest in the group but its recent development reflects Barkworth’s research interests and her role as both scientific and managing editor of the two grass volumes in the Flora of North America series. The herbarium served as both the editorial and production center for these two volumes. The materials provided were then used to develop two other publications, Manual of the Grasses of North America and Intermountain Grasses. Royalties from these publications have been critical to the herbarium’s subsequent development.

Slides Collection

The Intermountain Herbarium houses a photographic slide collection of over 1,000 slides. These are used in teaching and in making presentations. They are made available on loan to local students and faculty. Most of the images on this Web site are made from these slides; a few are from digital images and hence, are not represented by a photographic slide.

The initial development of the slides collection was funded by the Utah Agricultural Experiment Station. Most of the original slides were taken by Dr. R.J. Shaw, who provided voucher specimens for each of his photographs. The collection has since been augmented by other photographers, not all of whom have provided voucher specimens.

Anyone interested in determining whether the Intermountain Herbarium has a slide of a particular species should send an inquiry to Mary Barkworth. We do not have the resources to catalog the collection, nor to scan the entire collection.

Library

The Intermountain Herbarium houses a small, but high quality, non-circulating reference library. Its holdings are catalogued by, and included in the catalog of the main library of Utah State University, the Merrill-Cazier Library. The resources of the Intermountain Herbarium library can be accessed by research workers at other institutions through the InterLibrary Loan system. In addition, there are many reprints available.

Plants

The majority of specimens in the Intermountain Herbarium are of vascular plants (ferns, gymnosperms, and flowering plants). We estimate that approximately 2/3 are from the western United States, with at least half of those being from the Intermountain Region.

The best represented families are Poaceae (grasses), Scrophulariaceae (traditional sense), and Asteraceae (composites or daisies). These are also among the families with the largest number of species in the region; the Herbarium's holding reflect this fact, and also the interest those associated with the Herbarium have had in these three families.

There is one cabinet of bryophytes, many of which were collected by Seville Flowers, author of Utah' Mosses and Hepaticae of Utah.

There are two cabinets of type specimens. We are currently reviewing the status of all specimens in the cabinets, removing those that are not truly types. For those that are types, we are noting which kind of type they are and attaching a copy of the relevant publication. Once this task is completed, we shall make the listing available on the Web.

Type Specimens

Type Specimens At UTC

Type specimens are the specimens that "anchor" the meaning of a name. They can be considered voucher specimens for a name. There are various classes of type specimens. The most important are holotypes, lectotypes, neotypes, and epitypes. Syntypes are arguably the next most important, followed by syntypes. Isotypes are duplicates of a type specimen. One can be more specific and classify isotypes as isolectorypes, isoneotypes, isosyntypes, etc. but we, along with many other herbaria do not do so.

We are currently creating a database of our type specimens, checking the class of each type. A preliminary summary of the herbarium's holdings is presented in the following table.

| Type | Fungi | Lichens | Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holotypes (including photos) | 2 | N/A | 57 |

| Isotypes | 8 | 1 | 1049 |

| Paratypes | 81 | N/A | 75 |

Other TYPES and Type photos

Plant: 38

Classes of Type Specimens

Holotype: The person(s) first proposing the name stated which specimen was to be regarded as the type specimen. Current rules require that one state exactly which specimens one means and identify the herbarium in which it has been deposited.

Lectotype: The person(s) who first proposed the name did not designate a type specimen (this was legal prior to 1958) so someone else did so later. There are (as you might expect) strong recommendations about how one selects a lectotype. To find out more, consult the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.

Neotype: Sometimes holotypes and lectotypes are lost or destroyed. The most notorious instance of this was the destruction of all the types in the Berlin herbarium by allied bombing during World War II. When a holotype or lectotype ihas been destroyed or lost, a replacement specimen can be designated as the type specimen. The replacement type is called a newtype. And yes, there are some recommendations as to how neotypes should be selected.

Epitypes: Sometimes it is found that the existing type of a name does not have the features needed to distinguish it from other species. This happens sometimes when the original type specimen was a drawing (no longer legal except for fossils) or when it was not appreciated that what was being called a single spcies is actually two or more different species. In these circumstances, an epitype can be designated for the existing name. It must be consistent with the original use of the name. This then permits other specimens to be selected as the types for other names. Obviously, the specimen selected as an epitype should show all the characteristics currently used to distinguish the taxon involved from the taxa with which it had been confused.

Syntypes: In the bad old days when it was not necessary to list an individual specimen as a type, many taxonomists simply listed several specimens that they considered should be called by their new name. These specimens all have equal standing so far as being types are concerned and are called syntypes. Syntypes are sometimes called cotypes.

Paratypes: If a taxonomist lists several specimens as representing his new name but designates one of these specimens as the holotype, the non-holotype specimens are paratypes.

Isotypes: These are simply duplicates of a type specimen. They become important if the holo-, lecto-, neo-, or epitype is destroyed because they are the first choice as a replacement type (a neoneotype? theoretically possible).

Topotypes: Specimens collected from the same location as a type specimen. They have no nomenclatural significance.