Data Collection

Statistics as an area of study came from two seemingly unrelated areas of thought: probability and data collection. Although they are often taught as distinct units or chapters, both areas developed simultaneously. One of the first recorded instances of data collection was performed by William the Conqueror (d. 1087), who was the duke of Normandy and the king of England. In 1085, he decreed that data be collected and recorded on manors in England, such as the size of each property and how many teams of oxen were owned. The information was sent to Winchester where it was compiled in two volumes known as the Domesday book. There is speculation that the data was intended to determine tax rates, but William died in 1087 before he could use the information. Although the data collected was abundant, very little was learned from the data because even primitive forms of analyzing data had not yet been developed.

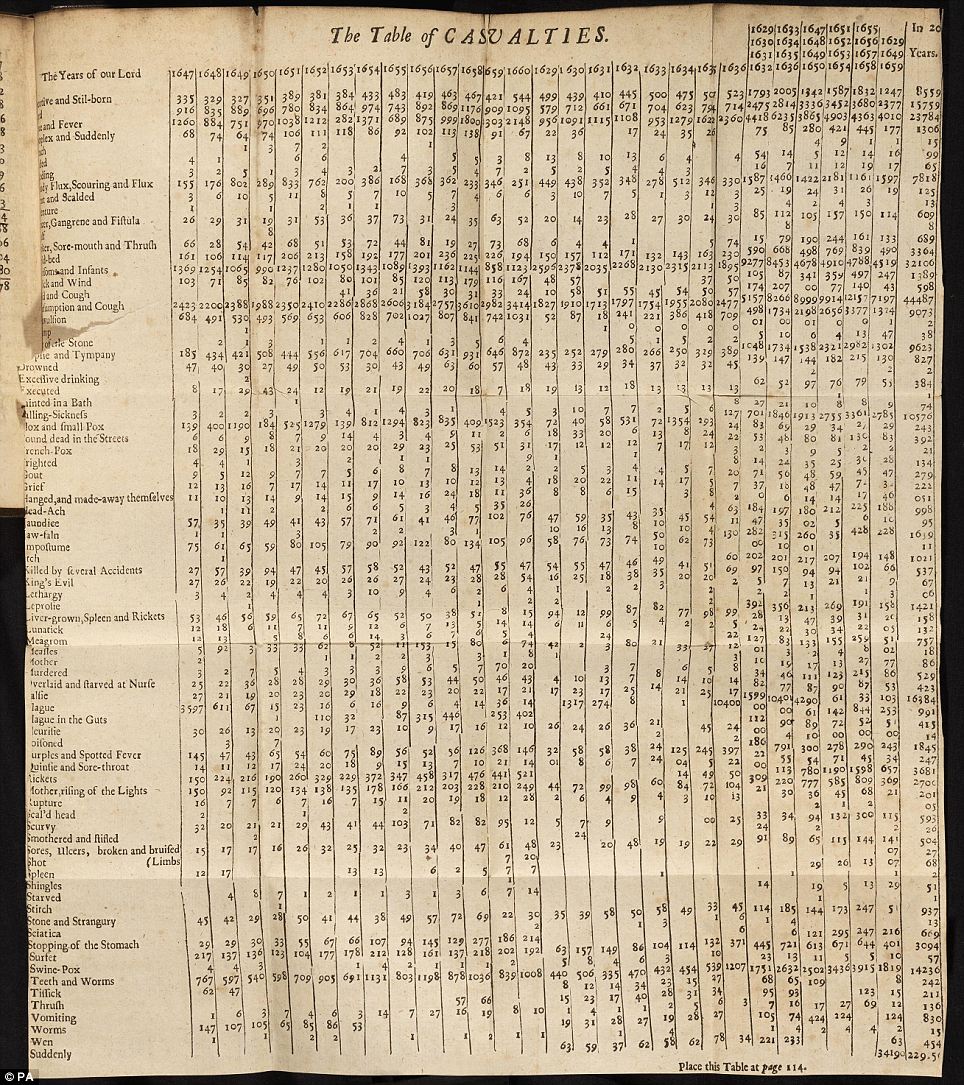

John Graunt (1620-1674), called by some the Father of

Statistics

, contributed to the significance of data collection

by exploring and summarizing available data. He looked at church

records of London parishes which were likely recorded to keep track

of the plague. He made some observations based on these records,

including some unexpected observations, and guessed at reasons for

such deviations.

Francis Galton (1822-1911) was another contributor to the progress of data collection. He inherited money at age twenty-two when his father died, meaning he no longer needed to earn a living. He spent his time dabbling in measurement and statistics by collecting data on people's physical measurements such as nose length, limb lengths, and features of fingerprints (which led Scotland Yard to begin to use fingerprinting).

Galton joined forces with Raphael Weldon (1860-1906) and Karl Pearson (1857-1936) to establish a journal called Biometrika, funded by Galton and intended to collect data to prove Charles Darwin's theory that species are created through evolution and survival of the fittest. Even though it would be impossible to see generations to observe the emergence of a new species, they hoped to see a change in the distribution of measurable characteristics of populations. Karl Pearson took over as the sole editor of the journal in 1911 when both Weldon and Galton had died, and scientists continued to submit data to the journal to be published. Some of these data sets are accessible in the statistical software, R. Pearson assumed that with enough data, the distribution would accurately represent the entire population. However, people who submitted data generally collected only the most accessible data, often giving a skewed version of the population.

Ronald A. Fisher (1890-1962) contributed to Statistics in many ways, but one way relevant to this section is his work done at Rothamsted Experimental Station studying crop variation. In his second study published while working there, Fisher summarized one example of his contributions in studying fertilizers in a field. Data had been collected for years simply by using different fertilizers on different fields or on the same fields in different years. However, this made the years of data relatively useless since differences in the results could have been due to the different conditions among fields or between years rather than the different fertilizers. He proposed to split the field into blocks and apply treatments to the blocks. Some may have suggested a pattern, such as applying each treatment to alternating blocks, but Fisher argued against this, pointing out that there could be some kind of fertility gradient across the field, meaning that the group that always has squares slightly closer to the side at the high end of the gradient would have a higher yield than it should. Since there is no way of knowing which direction this potential fertility gradient would run, Fisher proposed random assignment, which is now recognized as a key feature of good experimental design.

Fisher also published an article, Mathematics of a Lady

Tasting Tea

which considered a hypothetical scenario where a

lady claims she can tell the difference between tea with the milk

poured first versus with the tea poured first. He discussed the way

to set up a test to see if she's right. One way is to pour half of

the eight cups tea first and the other half milk first and see if

she can guess correctly (a $1/70$ chance). However, she has an

advantage knowing that there are exactly four of each. Another idea

is to randomly assign each cup to milk or tea first so there is no

way for her to know how many there should be of each, making the

chance of her guessing all cups correctly by chance $1/256$.

However, there is also a chance that all the cups would be the

same, so even if she got them all right, it might not show that she

could discriminate between the two. Fisher argued that there is not

a best

experimental design, but that the researcher must

decide the design based on their research aims.

During the 1920s, researchers debated the best process for selecting a representative sample. One idea was a random sample, where participants are chosen through a chance process, while another was cluster sampling, in which the population is divided into groups and entire groups are selected to make up the sample to represent the population. Jerzy Neyman (1894-1981) proposed stratified random sampling where the population is split into groups and the researcher chooses proportionate numbers of participants from each group, allowing the sample to reflect proportions of a population characteristic in the sample.

As described earlier, Karl Pearson favored opportunity samples

where researchers collect data on the most accessible individuals.

Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis showed that opportunity samples are

not representative of populations of interest because there can be

systematic differences between accessible and inaccessible

individuals. He worked to find the best sampling method. One method

he considered was a judgment sample

(also called a quota

sample

). In a judgment sample, the researcher determines the

characteristics of the population and then collects a sample that

matches the same characteristics. For example, if one third of the

population is Hispanic and one half are female, then one third of

the sample should be Hispanic and one half should be female. This

method eliminates factors that would influence the results because

the factor has the same effect on the population as it does on the

sample. However, it is difficult to account for every important

factor, both because the researcher may not know all applicable

factors and may not know their frequency in the population.

Mahalanobis found that a random sample would yield results that are

most likely slightly wrong, but one can estimate how far off to

expect the estimate to be. He became a friend to Prime Minister

Jawaharlal Nehru at the start of the new government in India. Nehru

attempted to mimic the central planning of the Soviet Union, but

unlike the Soviet Union, he looked at and published true

statistics, focusing on fixing government issues to avoid economic

collapse as the Soviet Union experienced.